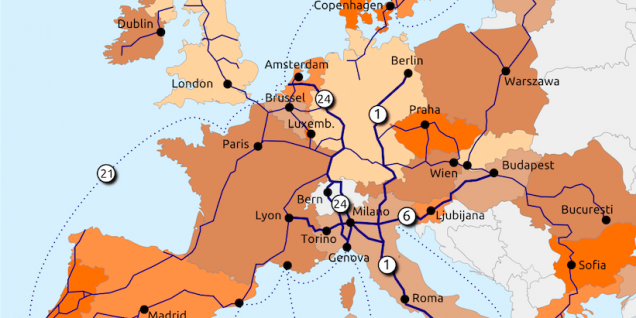

(photo: the Trans-European Networks infrastructure corridors, as proposed in 2005)

– by Andrew Spannaus –

Europeans are waiting for Juncker: the Juncker Plan, that is. In November 2014, a few months after his election as President of the European Commission, former Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker announced what appeared to be an ambitious plan for infrastructure projects that would break the cycle of austerity and deflation throughout Europe.

The original goal was to mobilize 315 billion euros (close to $400 billion at 2014 exchange rates) for projects around Europe, with a focus on transport, energy, research, and training. Of the total, 240 billion was to go to “strategic projects,” and 75 billion to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Most of the funds were not to come from public sources though; only 21 billion would be provided by the EU budget and the European Investment Bank (EIB). That capital would be used to issue bonds and raise funds on the market, and then create a multiplier effect thanks to the initial risk being guaranteed by the publicly-backed fund.

Juncker’s proposal came at a time when it was evident that the austerity policy imposed on much of Europe through what is known as the Troika – the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund – had not only failed to balance budgets in the EU Member States, but had contributed to a sharp drop in economic output, especially in the countries that had most aggressively implemented the “structural reforms” demanded by the supranational institutions.

Under the EU’s budget rules, individual countries are unable to increase their spending without cutting elsewhere, so it was essentially impossible to create economic stimulus without outside intervention to provide a jump-start, especially during a period of dangerous decline. That intervention was supposed to be the Juncker Plan.

But it soon became clear that even the public money to be mobilized would be found mostly by shifting funds from other sources, such as European programs for basic scientific research, and simply changing the name of funds allocated by the EIB. Nevertheless, Juncker and European political leaders held out hope that the Plan would do for them what they were unable to do on the national level due to financial constraints.

One year after the actual start of the plan, on June 1, 2016, the European Commission loudly claimed success, and proposed extending the Plan beyond its scheduled end in 2018. Commission Vice-President Jyrki Katainen touted the financing of SMEs and start-ups in particular, while it was announced that the special vehicle created to implement the plan, the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), had provided € 9.3 billion in support for major infrastructure projects.

If the number seems small, well, that’s because it is. 9.3 billion is better than nothing, but it doesn’t make a very big dent in the estimated hundreds of billions of euros needed to accelerate modernization of infrastructure connections throughout Europe. Furthermore, given that some of the money has just been shifted from one account to another, it’s understandable why the type of broad economic stimulus promised as of the Plan’s announcement doesn’t seem to have materialized. Economic growth for the EU as a whole has actually slowed in recent months, down to 0.3% in the second quarter of this year. And it’s easy to see how external factors such as the weaker euro with respect to the dollar and the turmoil in emerging markets, have played a significantly larger role in determining economic performance than have the policies of the European institutions.

The investment gap in European economies thus remains, prolonging the current state of stagnation. But the situation also offers opportunities for private investment to fill the gap. One way to stimulate such investment is through the use of public guarantees. The Bruegel think tank in Brussels, for example, has suggested expanding the EIB’s activities by using the basic concept of the Juncker Plan, i.e. contributing only a portion of the funding for large projects while acting as a coordinator to involve other financiers.

Another way the gap is already being filled is through bilateral deals with non-EU countries, a phenomenon that has been growing in recent years. The best example is that of China’s large investments in transport infrastructure in the Balkans region. The country that has suffered the most from the European crisis and the austerity policies in recent years, Greece, seems to have recognized that in the current climate, this is their best option. Greece has made deals with China, allowing it to invest heavily in the port of Piraeus. China’s goal is to make Piraeus the main entry point for Chinese goods through Southern Europe, and Chinese plans to also modernize the rail network connected to that port have led to a flurry of interest from international companies to invest in the region.

September 19, 2016

English, Notizie